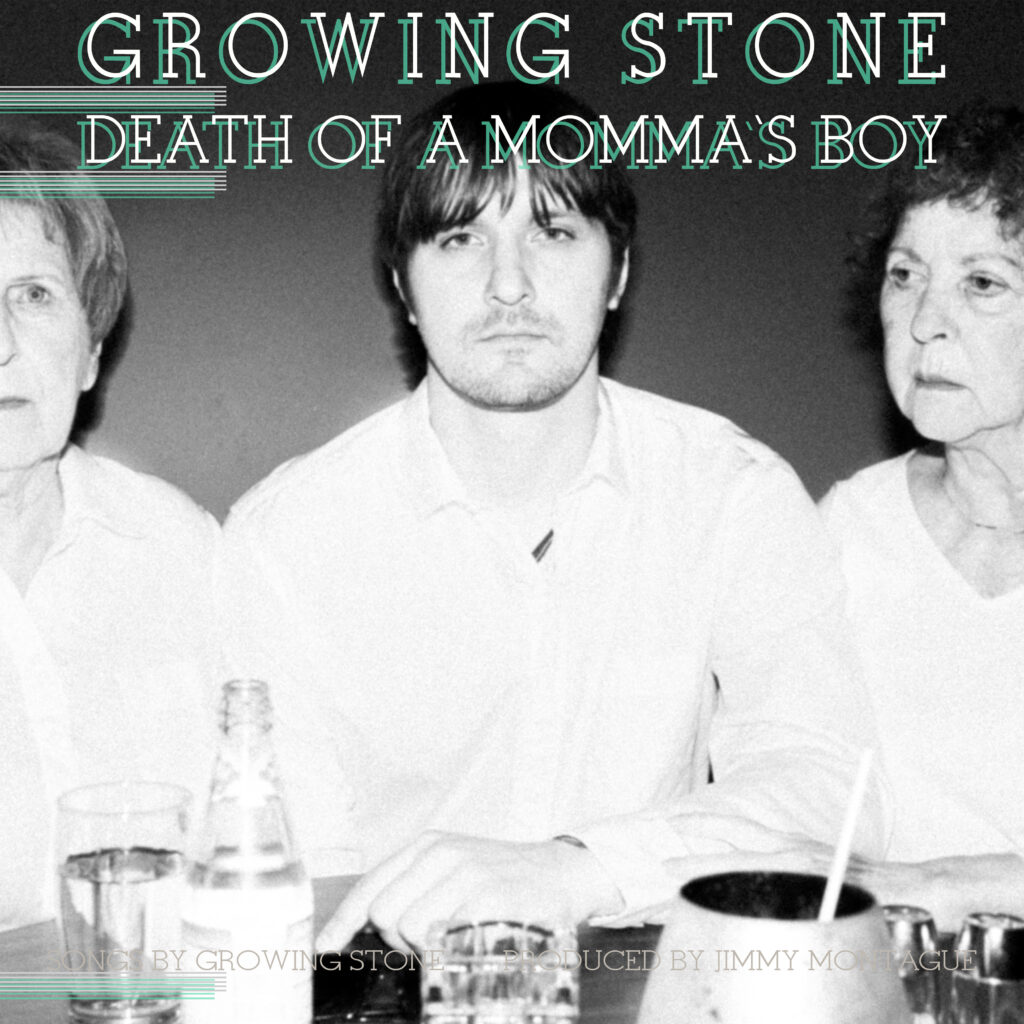

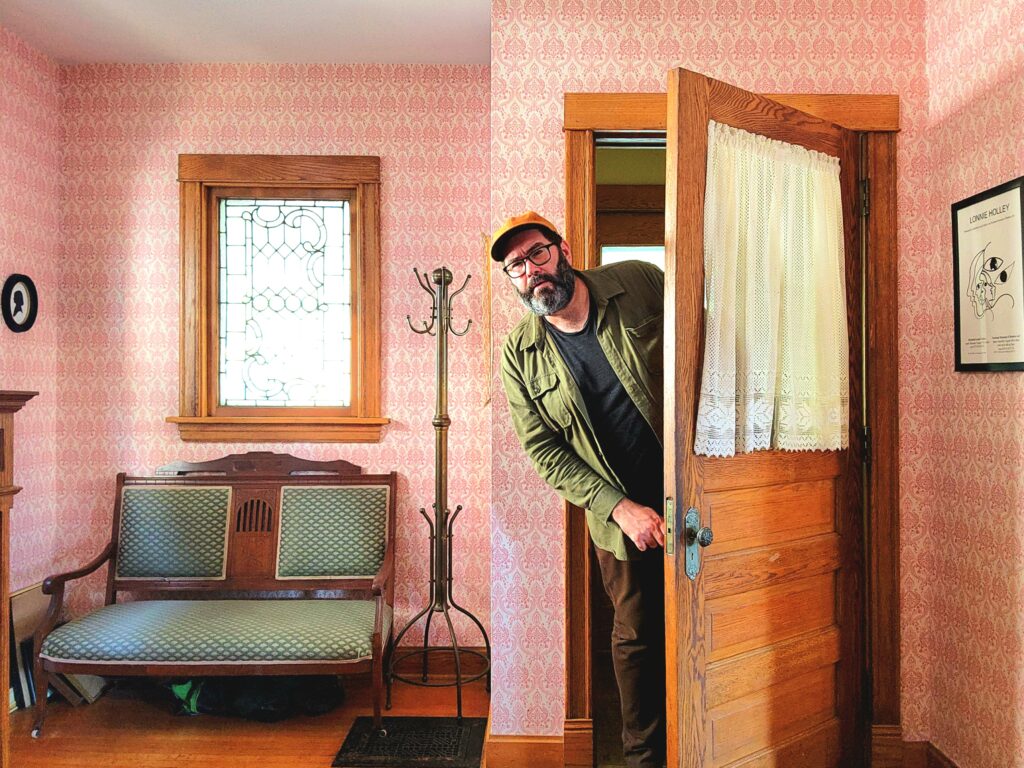

For years now Skylar Sarkis has been one of the most unique voices coming out of DIY punk, specializing in music that’s equal parts cutting and catchy. Much of this material has been through his band, Rochester, NY cult heroes, Taking Meds, but with his solo project, Growing Stone, he’s been proving that incisive and intense music doesn’t need to rely on volume. Growing Stone’s sophomore album, Death of a Momma’s Boy, is powered by a striking emotional honesty, a willingness to look so unflinchingly at discomfort and despair that the beauty around the edges starts to shine through brighter.

Since 2018, Growing Stone has served as an outlet for Sarkis to explore a different side of his songwriting. “This has always been the project that I’ve felt the most free in,” he explains. “There aren’t a ton of rules, except for the ones that I want to impose. It’s just singer/songwriter music so the lyrics are the focal point.” Death of a Momma’s Boy follows 2020’s I Had Everybody Snowed and feels like Sarkis coming into his own within that singer/songwriter identity. “Punk was the reason that I got into music in the first place, but I think singer-songwriter stuff is the reason that I’ve connected with it as deeply as I have,” he says. “I’ve always played in bands because I more or less know how to navigate that world–but I’d like to learn how to navigate this one.”

Recorded/produced by James Palko Death of a Momma’s Boy is built around Sarkis’ creative confidence, with recordings that vacillate between spare, ornate, or even menacing–sometimes even within the same song. “I think as a whole the record is more stripped down and raw sounding,” he says. “There’s a lot less drums. There’s no tuning on the vocals, we grinded for every take. Keys are more prominent because James is a great piano/organ player. It’s not as ‘big’ sounding.” The result is a record that amalgamates Sarkis’ influences (knotty, heartrending songwriters like Smog, Sun Kil Moon, Sparklehorse, and Mount Eerie) and filters them through his worldview into something new. “To me, the music is sadder than on the last album. I don’t know if that will register with people because the last album was pretty much completely about being an active alcoholic and that went over really well,” he wryly adds.

Death of a Momma’s Boy begins with the one-two punch of “Apple Church Rd” and “The Keep,” two songs driven by brittle drum machines, fingerpicked guitars, and Sarkis’ warm voice. The tracks are something of a misdirect, with bright, poppy melodies that ease the listener in before “Country Song” and “Dishes” take on a more solemn tone, matching Sarkis’ sharp observations on trying to rebuild after years of navigating through addiction. “This record was completely written in sobriety,” he explains. “Both Growing Stone albums are about pain, but this pain feels less diluted to me. It’s about feeling the actual pain, not feeling the consequences of avoiding it.”

The album operates from this place of bone-deep candor–not just lip service to the idea of vulnerability, but songs full of real warts-and-all soul searching that can be as challenging as it is moving. “When you’re used to being a trainwreck, you surround yourself with people who are okay with that,” Sarkis says.”Then you stop drinking and those people slowly start to let you down, and then you go out in the world and start letting normal people down. It’s humbling and it’s hard not to throw a pity party for yourself. You have to change and you don’t get an award for it, because all you’re doing is becoming a baseline considerate and respectful person.” Mid-album standout “Spring In New York” captures this mixture of frustration and contrition. It’s a snarling, down-tuned left turn that seagues into the stately-yet-hostile ache of “The Gym” where Sarkis starts with the simple idea of going for a workout and expands it into a winding and discomfiting story of regret and anger.

Death of a Momma’s Boy comes to a close with “Ballad of Growing Stone” and “The River Keeps The Pull,” two songs that perfectly capture Sarkis’ ability to pack a massive emotional punch with the sparsest arrangements. Every finger movement from fret to fret rings out, the vocals recorded so close to the mic that you can hear the hiss of the air in the background–all while Sarkis sings of hopelessness and beauty with a kind of reverence for the power of both. “If I can’t say something pretty, why should I say anything at all?” he asks on the album closer, and as it concludes with a wave of sweeping strings you’re left wondering the same thing, suddenly looking at your place in the world and considering the way you interact with it. It’s a fitting way to end an album focused on the innately human need for meaning and connection, and the innately human fallibility that often makes those things feel out of reach. “People like music like this because it reminds them that they’re not alone,” says Sarkis. “That’s huge. I don’t think we’re always good at community–but sometimes it finds its way to you.”