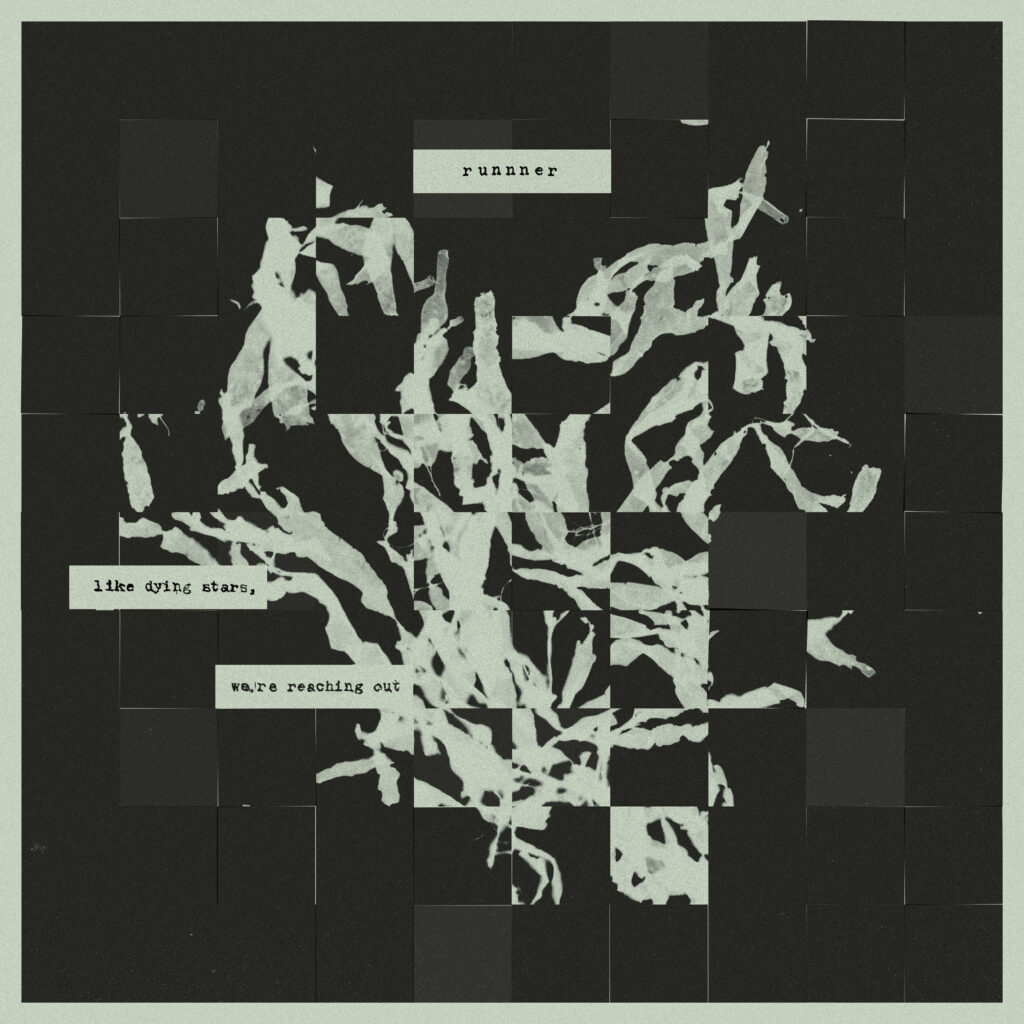

For the last five years, Los Angeles-based musician Noah Weinman has been Runnner, and for much of those five years, Runnner has been working. Working on his 2021 collection album, Always Repeating; working as a producer on the Skullcrusher records; and, of course, working towards his debut full-length, Like Dying Stars, We’re Reaching Out. From LA to Ohio and the Northeast and back, he’s been deep in the craft of sound. This is music made at home, using anything and everything: cell phones and handheld tape recorders, the hum of an a/c unit, voicemails from friends. Rubbing cardboard together, stretching acoustic sounds out to near liquid, or stacking delay pedals at random to scramble the smoothness of a song can make something known into something unknown–something ordinary into something cosmic. These are songs where the edges have been left deliberately rough because perfection invites predictability, and imperfection imbalances, and those imbalances ask the listener to listen again, and again. And in that listening, the sound can become earnest, can ask a question, can hold a conversation.

“I was sifting through my demos trying to decide what songs would go on the album, and I sort of started to notice this theme about the limits of language,” explains Weinman. “You’re trying to articulate something to someone, and it either doesn’t come out right or you end up not saying anything at all. It’s a pattern I see in my life, just having a hard time expressing myself to the people I’m close with.” So it’s no surprise that from a young age, Noah was drawn to other modes of expression: first studying trumpet and jazz, then falling into guitars, banjo, pianos and synths, and along with them discovering a love for stitching together songs and recordings. “It wasn’t until I got out of the studio environment and started recording at home that it became something I really love doing,” he says.

Like Dying Stars, We’re Reaching Out is the result of years of writing, recording, and tinkering in Weinman’s home, a lovingly crafted patchwork of organic instrumentation and otherworldly digital manipulation. The unexpected sounds and lush production elevate Weinman’s already impressive skill for melody and warm vocals, always pivoting between sparse intimacy and sweeping grandeur at the right moments. “I think I just want to try to make sounds that are a little original, that you couldn’t easily identify,” he explains. “But I get there by keeping my options pretty limited. I only have one input, so I don’t record things in stereo; I only have about three microphones and a few instruments, and I try not to use MIDI. I keep the ingredient list short, but that pushes me to be more creative in the genesis of certain sounds.”

This musical approach is reflected in Runnner’s lyrics as well, where the familiar is made unfamiliar, and then familiar again. With humor and heart, Weinman sifts through isolation and anxiety in the everyday: ruining the rice, buying shampoo, the way boredom and loneliness are tangled up together. And from these fragments, he makes something new, but also something already known and felt at once. “A lot of the songs have this narrative arc of rising tension that just leads to me not saying or doing anything,” he says. “It’s like there’s a signal loss between thought and speech.” Tracks like “i only sing about food,” “raincoat,” or “chess with friends” explore these different mental and sometimes even physical barriers to communication, while skittering drum beats and scrappy acoustics guide the listener through Weinman’s crowded thoughts. On mid-album standout “runnning in place at the edge of the map,” Weinman likens his catatonic self on the couch to a video game avatar stuck at the end of its digital space with nowhere left to go–tying the image to our desperate attempts to be who we want to be, despite knowing that our attempts will fall short.

Often Like Dying Stars, We’re Reaching Out sounds like life caught inside a moment, unsure of what comes next, but there is hope and lightness here too. The album’s final track “a map for your birthday” closes with the lines “like dying stars, we’re reaching out / so much i can’t say / but you nodded anyway.” Despite our inability to be what we want to be, to know where we are going, feel we belong, to be present, and to present ourselves fully and completely to the world, Runnner offers that perhaps it’s this longing to know one another, to understand each other when we’re incoherent or when the words just don’t come, that just might connect us.